Slow Players #27: "Buttons Like the Eyes of Fish" (Clune, Brodkey Revisited, Beha, etc)

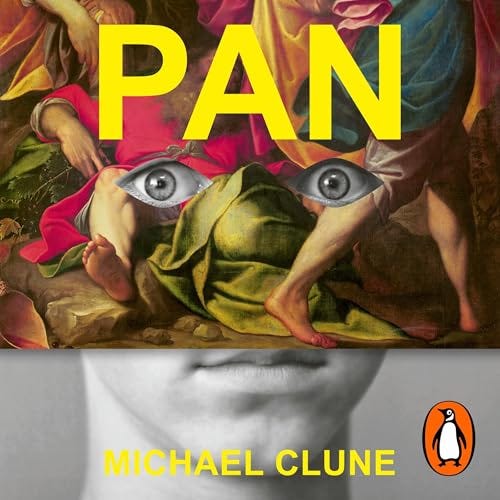

I reviewed Michael Clune’s new novel, Pan, for the Washington Post. Spoiler: I did not dislike it.

I’ve been thinking, still, about Harold Brodkey. My previous post seems to have given the impression that I dislike him, or at least that I dislike his work. Fair enough: I did say that I’d never been able to finish The Runaway Soul and Stories in An Almost Classical Mode, his twin magnum opii, and I was pretty hard on his public persona, although I did note that the latter was charming (which it was, far more than you might imagine of a man given to rather grand pronouncements on his own talent). The thing is, I do like the work: not “finishing” those two books (which are in some sense—and I mean this as a compliment, i.e. not strictly from a reader’s perspective—unfinishable, or perhaps a better word would be inexhaustible) doesn’t mean I haven’t spent substantial time with both. I’ve read much, probably most, of both more than once and enjoyed them, although I suspect “enjoyment” isn’t the primary thing one is meant to derive from Brodkey and I still don’t think that “Innocence,” the fabled cunnilingus story, gets over, at least not for me. But there are writers, many of them among the greatest, whose body of work consists largely of multiple attempts on similar, or even identical, narratives, writers who effectively . . . I won’t say “wrote the same book over and over,” but orbited certain knots of experience so obsessively that the books contain significant repetitions. Marguerite Duras, possibly, is one such writer; Jean Rhys, definitely, is another. I am, I suppose, one of those writers myself, but in any case one finds echoes and rehearsals of previous or subsequent books in Melville, in Conrad, in Dickens, in Roth, in Kafka. Certainly one finds them in Henry James, maybe the ultimate such writer. (I’ve read The Golden Bowl three times, but have I “finished” it? God no. That book is unfinishable, in the best sense.) Which isn’t to be lawyerly, but Brodkey is for sure such a writer to the utmost. He told the same story over and over (the cunnilingus part only once, I think, but even that exists in multiple iterations), to an effect that was both—intentionally—taxing, sometimes overwrought, occasionally torturing certain points of contact to the edges of coherence but also very often astonishing. Since the last post wasn’t sufficiently clear on this point I’ll emphasize: Brodkey was good, actually.

One dyspeptic commenter on the previous post took exception: he seemed to be under the peculiar impression I was writing a formal review instead of, uh, a newsletter, and proposed that writing a piece wondering whether many writers might be better served by posting and promoting a little less was contradictory. (“If writers would be better served by silence, this essay isn’t helping,” was the gist of his complaint.) While it was cool to encounter a real live Mr. Gotcha in the wild (although I will admit his long comment brought a different meme to mind while I glanced at it), I was more swayed by a few other folks who weighed in with thoughtful appreciations of Brodkey. One, in particular, encouraged me to seek out a story called “Play,” which I may have read long ago (at times it can be hard to tell with Brodkey, given how often the same scenario can be enacted in different stories) but most probably not because “Play” seems unique—and memorably disturbing—even within Brodkey’s singular and often uncomfortable body of work. “Play” (the story is included in Stories in an Almost Classical Mode) is—there’s no other way to say this—a rendering of a pre-pubescent boy’s sudden sexual awakening in the presence of an even younger boy. Which is to say it’s a story that’s none too easy to talk about, let alone “recommend,” in 2025. It’s fucked up! On the basis of its subject matter one might be very much disinclined to spend time with a story like that. But leaving aside the fact the experience it treats is extremely difficult—is essentially the molestation of a seven-year-old by an eleven-year-old—the story itself (which thankfully isn’t graphic or even vaguely descriptive of what goes down until the very end, and even then in terms that are pretty elliptical) is good. Which is one of those distinctions that shouldn’t really require exegesis, but given that we’re still in an era where some people get squeamish about watching Polanski movies or reading Lolita (which is certainly no less specific than Brodkey’s story) I’ll go ahead and make it for clarity’s sake.

“Play” begins with two children under a bed: the narrator (the first sentence makes clear that this is a memory: “Sometimes, when I wake, I am eleven years old”) hanging, suspended, from a boxspring, climbing horizontally from coil to coil (“no part of me touches the floor”) while the younger boy, clad only in his underwear, clings to his chest. It is, for sure, a claustrophobic and perturbing scenario: the narrator is also mostly naked, and you can feel the boxed-in discomfort, physical and otherwise, of the whole scenario: “The bed-springs are a matted tangle of jungle growth; sweatily, intensely, I disturb the dust of habitation in the half-growth beneath the bed.”

Brodkey excels at these kinds of claustrophobic, half-exhilarating and half-nightmarish encounters between bodies. His stepfather’s embrace in “His Son, in His Arms, in Light, Aloft” is similar: the blend of adoration and terror there is intense, and is central to whatever experience Brodkey was trying to work out, over and over, in these stories. That’s what I mean when I say Brodkey may have had other things on his mind than “enjoyment”—these stories are grappling with some of the most intense horrors and problems that can exist in human relations—but fortunately here the narrator spirals away from this immediate situation into a broader contemplation of what “play” consisted of for the narrator and his cohorts, in and around the neighborhood, the games of stickball, football, Robin Hood, Tarzan, Space Search, Torture, etc (etc, etc, etc . . . etc) he and his cohort engaged in in approximately 1941 (the story never specifies a year, but one may assume the narrator’s age corresponds roughly with Brodkey’s, who was born in 1930). Most of the story consists of this: cataloguing and examining what these neighborhood kids got up to in ways that are insightful, funny, graceful, goofy. We don’t return to the younger boy, Randolph, and the scenario underneath the bed until we’ve gotten an extensive accounting of these various forms of play, on their undercurrents of both innocence and sadism, on the fact these kids are of course too young to have—or even understand—a fully adult vocabulary: “fuck was explained to me at least fifty times by older boys, but I hadn’t the faintest idea what it meant . . . We lived in a sensual and passionate immediacy, as if the suburb were a walled and gated garden.” Nothing about this section is particularly difficult. If anything, it’s frequently lush, gorgeous, as with this characteristic sentence:

The blue jeans lie on the floor, the slightly smelly, stained sneakers, socks, the flimsy, discarded shirts, twisted, outspread, frail, their buttons like the eyes of fish.

How good is that? It’s fucking perfect, somehow, moving from all those jumbled-up and stinky sneakers and socks to the bright delicacy of those “flimsy . . . frail” shirts to land on a startlingly apt yet surprising metaphor. This story, like all of Brodkey’s stories, are filled with sentences like that (I’d say “he could write them in his sleep,” only he worked them so obsessively he clearly did not), and each one might be worth more than many writers’ careers.

Of course, the story has to return to that scenario under the bed—it holds its tension throughout because we know we will, we must—and when we do, the story zeroes in on its primal catastrophe: the narrator scissoring Rudolph with his legs until he arrives at his, uh, epiphany: “Five closely attached ascending sensations disconnected me . . . I was on the edge of a vast black emptiness . . . And I went over a—a thing, tumbled over the round globe, and off into the darkness, scattering warm, strangely liquescent sparks, uncolored but scorching: something scorched me; I felt something like a wire whip through me; it was drawn through me and then from me, eviscerating me; I was thrown into grief, into astonishment, into a strange nothingness, a blankness of feeling unlike anything I’ve ever known.” On the one hand, what? (“five closely attached ascending sensations?”), but—of course—we know what he’s talking about, uncomfortable as it may be. He bangs the point home a few sentences later with a reference to the “dime-sized” spot that has just appeared on his skivvies.

Why write—or I guess the real question would be, why read—something like this in 2025? On the one hand, stupid question: we should for the same reason we always did, because a literature that doesn’t attempt to reckon with difficult questions and complicated (unsettling, traumatic, morally gnarly, etc) experience wouldn’t be worth preserving. But on the other, given that there are an infinite variety of writers to read these days—another generational layer or two has accrued since Brodkey’s time—it’s not unreasonable to wonder why pay attention to Brodkey, specifically? To which I would say, simply, that very few writers, then or now, have plumbed consciousness—the actual thing, the often deeply unpleasant experience of being alive—with anything resembling Brodkey’s depth and unstinting attentiveness, or who could do it with such excellence on the level of the sentence. In that sense, his peers (Roth, Mailer, Updike, etc) came nowhere close, and the comparisons to Proust or Faulkner, seem less unreasonable. Did he actually achieve the heights of the latter two? Not quite (although in places he comes awfully close). But then again, neither have you or I.

Funnily enough, Brodkey did write an essay that addressed some of the other questions that came up in my previous post, though. In that essay, titled “How About Salinger and Nabokov, for Starters?” (you can find it in a collection called Sea Battles on Dry Land), Brodkey wrote about fame, about whether the novel still mattered, about the distinction between a public, famous novelist and a consequential one, and whether it was even possible to be both. (Salinger and Nabokov, for Brodkey, were both.) But Brodkey had no real time for fetishizing the state-persecuted writer, as his buddy DeLillo perhaps did. In response to a comment by George Steiner (made when he appeared with Joseph Brodsky, Mary McCarthy, and AA Alvarez on a televised panel called “Do Repressive Systems Produce Great Literature?” in 1982), he takes note of the “ugly romanticism” of imagining artists in repressive systems might produce greater, or more dangerous, art. “A state-endangered writer is, willy-nilly, a more romantic object of contemplation and aesthetically a more satisfying one since the problem of aesthetics doesn’t quite enter in. But in time the aesthetic question does dominate,” Brodkey writes. In the end, “Writers do have to produce good books or go unattended to.”

This, of course, is true—inescapably so. It will be as long as writers and books exist. My friend Chris Beha wrote me last week and noted that the silence of a DeLillo or a Pynchon was effective precisely because its withholdingness offered a sharp, and attractive, contrast to the Gore Vidals and Norman Mailers whose self-promotive energies seemed even more inexhaustible than their creative ones. Chris put it well, in general:

No one can speak on behalf of silence. Only silence can do that job. The trouble with silence, of course, is that most people will never hear it--and those that do are apt to misunderstand it. But that has always been the case. I think we are wrong to imagine that silence, exile, and cunning are simply not available to us in the way they were to Pynchon or Salinger or Delillo or Gaddis. But I think this gets it wrong. After all, people back then actually listened to writers. How much more tempting, in the age of Mailer, to speak up. How much more obvious that speaking up was the only way to get read. It has always been the case that those who won't speak up on behalf of their work are more likely to be ignored. The thing that Pynchon and Delillo did was to write work so undeniable that they naturally became objects of fascination, people from whom others wanted to hear, and it was against this desire for availability that their withholding was put into noticeable relief. I don't see why that couldn't still happen now. All of that is just to say that the thing to do is write something truly great and let the chips fall where they may. But that has always been the thing, hasn't it?

Indeed. Always has been, and I suspect always will be, insofar as all the posting and promoting in the world won’t make a good writer out of a shitty one. Whether it can actually do the reverse is an open question, but there have always been show ponies and there have always been stallions, so to speak. I know which one I’d rather be.

Nicely done, Matthew.

Thanks for this deep dive into Brodkey, who I now feel I've read through your writing about him and will certainly check out of the library soon enough. I've known about him for years, but he was one of those significant writers who passed by me in my twenties when I was trying to read all the great American authors of the 20th century in one swoop. I didn't realize he was so ambitious and there is something to that that is undeniable in an author. These newsletters make me look forward to reading The Golden Hour (is that an allusion to Joan Didion in Play it as It Lays, when she writes about the sunsets and putting the children to bed?) Anyway, keep up the good work - your talent humbles me.