It’s not a very 21st Century mindset, I guess, but lately I’ve been thinking of how writers should be read but not heard. A rich sentiment, to be sure, coming from someone who’s been assiduously promoting a book these past few months—hey, here I am on the Team Deakins podcast, and here’s yet another marvelous review of The Golden Hour from The Spectator—but still. Marco Roth wrote a lovely piece recently about Harold Brodkey, and I found myself contemplating how Brodkey, who wanted nothing more than to be considered a giant in his lifetime (and, indeed, after his lifetime) is now largely forgotten. All of us will be, for the most part, so it’s no particular big deal for him to join the ranks of the obscure-but-occasionally-read dead, but . . . even by the standards of egomaniacal 20th Century writers Brodkey really took the biscuit.

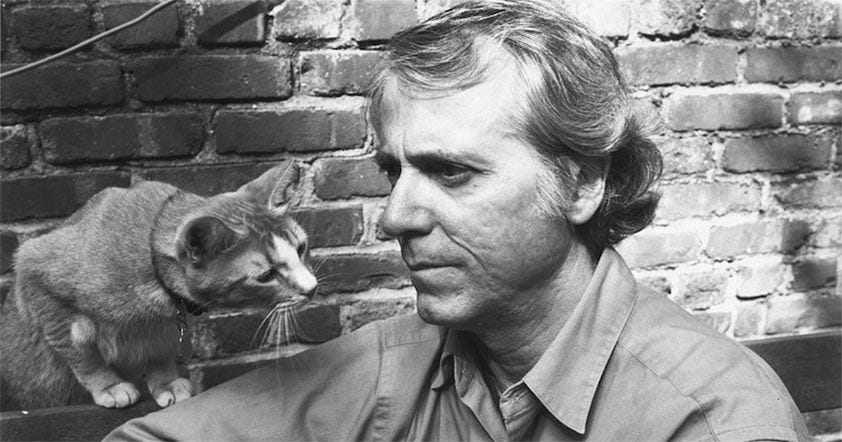

Look at this yoyo, my God. The eyebrows! The supercilious stare! For those who don’t remember—and I would imagine even within the well-read subscriber base of this newsletter there are those who might not—Brodkey rose to prominence (or some Manhattan-centric form of it, at least) with the 1959 publication of a short story collection called First Love and Other Sorrows and then spent the next three decades cultivating his own mythology via an unpublished novel called for most of its long-rumored existence A Party of Animals. This manuscript (one assumes he’s clutching a portion of it in the photo above) took on an apocryphal life of its own: it was thousands of pages long; it consumed eleven different file cabinets in his office; it was going to prove that he was “the rough equivalent of a Wordsworth or a Milton” and that Brodkey was “the best living writer in English” (Brodkey didn’t make these assertions himself, he merely claimed that other people had said so—many people are saying—every chance he got); it was shuttled from Random House (to which it had been sold upon conception in 1964) to FSG (in 1970) to Knopf (in 1979), refinanced every five- or ten years with a yet-larger advance, occasionally appearing as a forthcoming title in publishers’ catalogs but never actually completed to anyone’s satisfaction, or at least not the author’s, until some abortive, partial, or alternate version was ultimately published, having arrived back at FSG, under a different title—The Runaway Soul—in 1991.

Even that cover tells you something, with the title practically a footnote compared to the author’s gargantuan name. And this, it should go without saying, seems a miserable way for a book or a writer to live. Maybe it wasn’t—Brodkey wasn’t exactly a recluse, and still cut something of a figure, at least reputationally, through the New York I arrived in in ‘94—but to spend thirty years on a novel only to have it fizzle upon arrival is depressing. Then again, well, you should read the article that goes with that New York magazine cover above. What an insane portrait of late 20th Century American literary culture emerges! Brodkey insists that John Updike stole his mojo (by basing the figure of the Devil in The Witches of Eastwick on him), that Renata Adler did the same in Pitch Dark, that he wants desperately to be free of literary politics but that Lish, Mailer, everybody just won’t let him! Somehow the person in this article gets taken seriously, and not only by himself! But there is one bit that emerges which I find delicious. At one point, discussing the writer’s daily round of telephone calls (Brodkey was an inveterate gossip, of course, and it’s worth noting that for all the egomaniacal preposterousness of his persona the writer emerges somehow as improbably charming) it comes out that one of his phone confidants is Don DeLillo. “We talk mainly about writing and death,” DeLillo is quoted as saying. “Those are our twin subjects.” When Brodkey asked DeLillo how he might better manage his fear of death (a reasonable question to ask the author of White Noise) DeLillo apparently advised him to watch more TV. “It worked so well,” Brodkey says, “I went out and bought a huge new television set.”

Killer advice, obviously, Don. But I was struck, too, by the improbability of this friendship. Because if Brodkey was a guy who might have considered being on the cover of New York magazine a thing of some importance, DeLillo was one who shunned (or at least claimed to shun) the spotlight. While I was writing The Golden Hour DeLillo was much on my mind and I kept tacked to my wall a brief address he gave in 1997 on the Chinese dissident Wei Jingsheng. In it, DeLillo writes:

“The deeper they conceal him—the more remote the cell, the smaller the cell, the colder and stonier the walls of the cell—the more vivid and living is the writer.”

It’s easy enough to question this. A lot of DeLillo’s pronouncements on the role of the writer from this era have an air of radical chic to them—much talk that drifts a little close to the sort of thinking that averred the 2016 election was sure to usher in a new golden era of punk rock—but over and over he returns, in the scattering of interviews he gave through the late 1980s and mid-nineties, to the idea that a writer ought to be culturally marginalized, ought to avoid the glare of the spotlight, that the best thing for a writer to do was not talk too much. “I’ve always liked being relatively obscure,” DeLillo told the Times in 1991. “I feel like that’s where I belong, that’s where my work belongs.” Needless to say, saying this to the New York Times and saying it in private are two different things, and it’s reasonable to suspect that DeLillo (whom I’ve never met, but who by various accounts really is a soft-spoken and deeply private man) nevertheless may have been simultaneously engaging in a bit of image-management. After all, he wasn’t Pynchon—he did grant interviews, and has made public appearances—and no one who was also thinking as much about Warhol, about cinema, about television and about crowds as he was (these themes being all over his work, particularly in Mao II) could have neglected to consider his own public persona. But DeLillo also told the Times:

“It’s my nature to keep quiet about most things. Even the ideas in my work. When you try to unravel something you’ve written, you belittle it in a way. It was created as a mystery, in part. Here is a new map of the world: it is seven shades of blue. If you’re able to be straightforward and penetrating about this invention of yours, it’s almost as though you’re saying it wasn’t altogether necessary. The sources weren’t deep enough.”

This seems to me correct. And the fact that writers are by now forced (or at least expected) to be straightforward and penetrating about their books through endless q-and-as and niche podcast appearances—the posture of media refusenik isn’t really available anymore—is not incidental to the fact that no one in this country has written a book as good as Mao II, let alone Libra, in the three-and-a-half decades since. (Indeed, writers are these days invited to talk less about literature and more about their favorite taco trucks or luxury watch collections, a process that can’t help make even the ones who are good seem cheugy and embarrassing.) This is true in large part because that space for mystery—the expectation that a work of art should be one, in order to remain a work of art—has been obliterated. Obviously, any half-decent book eludes capture. We can say whatever we want about it, and the work of art remains whatever it is. But we do make them smaller, and ourselves dumber, by talking facilely about them, never mind that writers all essentially have to do so in order to be able to publish again. And when people lament or complain, here on Substack or anywhere else, about the state of the novel, whether it’s living or dead, whether men are reading them or not reading them, about whatever form of ideological or elite capture is dominating the discourse du jour, I always want to tell them this: that the problem is none of the above, but rather the fact that we should all stop talking, the better, as the late Shirley Hazzard said, to find out what we—or, better yet, what other people—actually think. Because the more literature, or at least literary culture, is reduced to the merely gossipy or discussible, the more it is boiled down to arrive at its ultimate 21st Century distillation, the creation of an ever expanding and increasingly meaningless series of lists (lists being something DeLillo correctly identified as “a form of cultural hysteria”), the less our literary environment can actually mean or matter to anybody. I have no idea what the “best” books of the 21st Century are and neither does anybody else—eventually, no doubt, history will arrive at some sort of maimed consensus that will surely be partially mistaken, but hopefully it will be better than this mostly lame and half-witted one—but I do know any number of great ones, most of them not represented on any such list (and the few that are certainly remain beyond the grasp of whatever capsule descriptions they’ve been assigned).

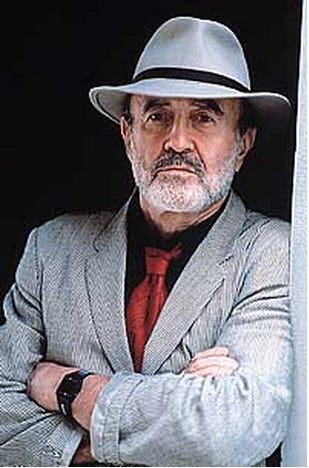

What about Brodkey though? Was the work any good or could he just wear the shit out of a Borsalino? The answer is, uh—and perhaps unsurprisingly—both. The Runaway Soul, and its companion volume of sorts, a brick-sized collection of stories that remixed and remodeled a lot of the same material under the title Stories in an Almost Classical Mode, which appeared two years earlier—is a mess. Both books have defeated me across multiple attempts to read them in their entirety. Both of them engage the adventures of one Wiley Silenowicz, a clearly autobiographical stand-in for Brodkey, and his adoptive parents S.L. (also sometimes called “Charley”) and Lila (sometimes “Leila”). Both of them are completely fucking exhausting (I defy you to make it through all thirty-one pages of his most famous story, “Innocence,” twenty-three of which are devoted—I chose my modifier there advisedly—to what is surely the longest description of a single act of cunnilingus ever written for publication or otherwise), and both of them contain sentences, paragraphs, pages on end that are totally amazing. Not amazing enough to prevent one from feeling exactly as Kasey Casem famously did once on a separate occasion, but amazing nevertheless. There is, throughout both books, a sense that Brodkey had been terrorized, indeed molested (neither book is explicit on this point, through Brodkey eventually would be) by his adoptive father, and a wildly vivid sense of parents as mythological giants, as demonic angels of both love and terror. (A story called “His Son in His Arms, In Light, Aloft” gives a good capsule sense of both projects.) They are, like most books probably, failures. They are also, unlike many books at all, shot through with glimmers of unmistakable genius, sentences so indelible I’ll never forget them. (An uncharacteristically short one that might be his best remembered—To see her in sunlight was to see Marxism die—is pretty great, albeit faintly goofy.) But like many (most? all?) people, Brodkey never really got over his earliest experience, his childhood elations and terrors. As he put it in what is probably his best, and certainly his most readable, book, This Wild Darkness, the one in which he is more explicit about the abuse he survived as a child:

“I am a genius, or I am a fraud. I am possessed by voices and events from the earliest edges of memory and have never existed except as an Illinois front yard where these things play themselves out over and over again until I die.”

If those two sentences were the only things Brodkey ever wrote they’d probably be enough to make him worth remembering. Because there, after all, Brodkey shoves aside whatever desperate assertions of his ego made him such a sad-yet-laughable figure to render something that is probably in some sense true for everyone, something so heartbreakingly stark I might never get over it myself. He died in 1996, and This Wild Darkness chronicles the diagnosis and the disease—AIDS—that killed him. One can imagine that this was not the work for which Brodkey would’ve most wanted to be remembered, but it is certainly one for which he ought to be, as Marco’s great piece also makes plain. There is one margin, of course, beyond which all writers are forced to stop talking, one obscurity from which even the solicitations of New York magazine can’t save us. But it would be nice if we were permitted to stop talking before then. I suspect our lives, like our literary culture, would be better if we did.

Make mystery possible again

Loved this. I often think that to make it in the literary world, one has to think of themselves as a sort of end of the bench player in the NBA--the guy who thinks he deserves to be out there, who knows that if he just gets his shot, he'll prove everyone wrong. This is the attitude of the player who gets garbage time at the end of the game and immediately starts launching three pointers, padding his paltry stats. This sort of delusional, irrational confidence is a paradox, because if you don't have it, you'll never make it, but so many people have it when it's unwarranted. Jeremy Lin is a positive example of this, I think (he famously waved off Kobe to take a last second shot) and the current example is probably Jonathan Kuminga.