Hello!

I’ve told this story before, but I suppose I’ll tell it again. I met Shirley Hazzard in the fall of 2000. I’d been hired to adapt her novel, The Transit of Venus, for Warner Brothers, after stalking it for a while. I walked into her apartment on E. 66th Street ostensibly to interview her for The Paris Review, but really I was there for anything I could get: wisdom, insight, whatever it is a young writer can ever hope to glean from meeting an older one. The Transit of Venus was then—it may be still—my favorite English language novel by a late 20th Century writer. I cannot think of one by a living person that might equal it, and I’m pretty sure that Shirley’s own temporal peers (let’s say, for the sake of argument, Toni Morrison, Philip Roth, Don DeLillo) might not have done so either. It is her only great book—the others are all OK-to-pretty good—but it is great in the truest, most reverberant sense of the word, the kind of greatness that might, if anyone still believed in this quality as anything detachable from capitalist hoarding, be spelled with a capital ‘G.’

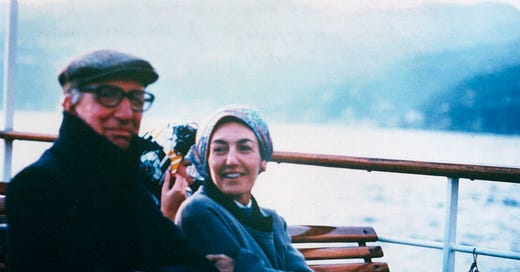

Shirley was a great person too (and here I am, once again, tempted to capitalize the ‘G.’). At the time I met her I wasn’t aware that she had been, among so many other things, the first person to blow the whistle on Kurt Waldheim’s concealed Nazi past while he was Secretary General of the United Nations (Shirley had worked at the U.N. herself for a period); I was merely attuned to her elegance, her manner, her—I hate this fucking word, but there’s not really a better one available—decency. She had a moral compass, and a clock, a sense that the time to act upon one’s kindest impulses was always right now. (Once, she made herself an hour late to an appointment with me simply because she had decided to accompany a bicyclist, a stranger who’d been grazed by a car, to the emergency room.) It is almost impossible to talk about her without wanting to drag out words that have been discredited, that seem, and perhaps are, flat-out ridiculous in our current moment, words like “nobility” or “gravitas,” ideas that appear to have been completely jettisoned and/or co-opted by right wing grifters and buffoons, even if this erosion of standards is in part (but only in part) what The Transit of Venus is about. I walked into her apartment, which was small, orderly and quiet, and we talked for a couple hours about writing, about literature, about Naples and Capri, where she lived half the year, and about the movies, although the seductions of Hollywood didn’t seem intelligible to her at all. We talked about her late husband, Francis Steegmuller (that’s him next to Shirley in the photograph above, which was taken on the vaporetto between Capri and Salerno in 1977), who’d died six years earlier but who remained present in the apartment, down to his overcoat still hanging on a coat stand and his British brand of toothpowder (not -paste) in the bathroom off the study. We talked about poetry, a lot, and Shirley quoted not just the obvious poets—Auden, Hardy, Keats—from memory, but also less obvious ones: George Crabbe, Leopardi, Arthur Hugh Clough. At some point I looked up at the painting above the mantle and realized it was (I believe) a Renoir, and she remarked that “Francis had picked it up in Paris after the War,” when such things were available.

I bring all this up because Shirley is having a moment. A new biography by Brigitta Olubas has just been published, and while I might not entirely be free of bias (I appear in it a handful of times), I reckon it is very good. More the point, I think it lights up both Shirley the human being (“noble” she may have been, but she was also given to occasional self-mythologizing, bouts of depression and disappointment, struggles with her family and so on) and the romantic figure. She was worthy of a biography, which is more than one can say of most human beings (or most writers even), and this particular biography is worthy of her, which is about the highest praise I can think of. Olubas’s book is one reason for this dispatch, but really . . .

A couple weeks ago I was walking in Victoria Park, in Hackney. A part of London Shirley probably never spent much time in (when she was there in the early 1960s, a period in which a memorable stretch of Transit of Venus is set, Hackney was still a poor and sometimes dangerous neighborhood), but nonetheless. It was raining, and I found myself with an English folk song ringing in my head, and I realized the song (“Blow the Wind Southerly”) is one hummed by the protagonist of Transit as he makes his way through the rain at the beginning of the novel. I haven’t read the book in well over ten years—the movie I wrote for Warner Brothers never happened—but certain books, of course, become a part of who you are. Certain books, and certain people too. While I was in England, Sam Bankman-Fried had just begun his spectacular, and ridiculous, implosion; Elon Musk was in the middle of announcing his Twitter Blue fiasco; the results of the American election—not quite as calamitous as my wife and I had both expected the day we took off—were still trickling in. It was, in other words, just a few weeks-that-now-feel-like-years ago (Kanye West’s Nazi affinities, like Kurt Waldheim’s, were still under wraps), but how could I not think of Shirley, really? The culture, the discourse, the attention-sucking actors on the American stage: these things are so fucking stupid they beggar belief, in ways, and part of the reason (though certainly not all of it) is that these future-sculpting geniuses appear to have never read a book. Of which, fine, fine—I, too, find my phone and the infinite number of choices offered by streaming services have eroded my attention span a little, and I certainly don’t believe in shaming people for what they do or do not read—but a total disinterest in history coupled with a straight-up inability to process larger blocks of information can only lead to disaster. In any case, I found myself wondering what Shirley would have made of these people, except—also—I didn’t have to wonder. Apparently, SBF did read a book once or twice, and came to the conclusion that Shakespeare was a “shitty writer.” One knows precisely what an inveterate quoter of George Crabbe who knew a large portion of Byron’s “Don Juan” by heart would have made of that. The same thing I do. (And, I would expect, you do too.)

Back to Shirley, though. Everyone who knows me, and a fair number of people who don’t, has heard me rave about The Transit of Venus before. I’ve been obsessed with it, evangelical, now, for decades. It’s one of those books I used to buy in bulk after I first read it in the mid-1990s so I could foist it upon people I’d just met. The book’s reputation at that time was in eclipse—Shirley hadn’t published anything recent (Transit had been published in 1981)—and while it’s moved in and out of eclipse since then (Shirley won the National Book Award after she finally finished the less-good The Great Fire in 2003, which touched off a fresh wave of interest for a while), it’s a book that seems often to generate a strange resistance in readers. In his memoir Intoxicated by My Illness, Anatole Broyard cops to the fact he’d been immune to its charms the first time around before returning it, as he describes, “with tears of gratitude in his eyes” and the hairs raising on his neck in his hospital bed while he was undergoing treatment for cancer. (Indeed, it was this description that prompted me to return to the book after I’d briefly put it down after my own first attempt.) More recently, Geoff Dyer, Michelle de Kretser (who went on to write a short, and very good, book on Hazzard herself) and Michael Gorra have all copped to abandoning the book once before returning to embrace the novel's overwhelming power, and Michael Ondaatje—another enthusiastic Transit partisan—recently confessed to me that he’d done the same. So I’m tempted to say, Don’t read it. Do not. Ignore it. Surely there’s another article about SBF, another idiotic gesture the world’s richest attention whore has unleashed upon his $44 billion plaything, another fascist who needs punching. You don’t need another recommendation from me. Do not read The Transit of Venus. (Reverse psychology is a feeble trick, but it’s worth a shot, right? You could also read Lauren Groff on the matter if you’re inclined to trust her word over, or along with, mine.)

Recommendations aside, why do people resist Transit? Is it because (as Broyard did the first time) they find it “too pure, somehow; too heroic; larger or finer than life, and therefore unreal?” Maybe. No one wants a lesson or a fairy tale—I sure don’t—and there’s a fineness to the writing itself that is potentially (if not actually, once one syncs with the book’s rhythms) exhausting. The book’s characters are endlessly in the throes of ecstasy or despair, and the fact that it dares us to imagine and to desire a happy ending is a little off-putting. (How many 20th Century novels, when you get right down to it—how many novels period—really do that?) Hazzard treats her major and its minor characters with equal precision, and equal detachment (which is where the book’s final, brutal, conclusion sources itself), and even an ordinary piece of business—a woman walking in a park—is described like this:

In a park without flower-beds or streams, on undulations of November leaves, Caro was walking alone. Branches fissured a white sky, the bark on ancient trees was corded like sinews of a strong old man. On a free afternoon given in recompense for late office hours, Caro had come there without purpose, scarcely noticing the intervening streets crossed in her mute private delirium. Inside the park, lack of intention struck her wretchedly, and she grew physically uneasy, ears aching from cold, feet slipping on dun leaves. The smell of earth was decayed, eternal. Flat colours offended, a dreariness full blown: Nature caught in an act of erasure.

See what I mean? It’s just a little much: the diction is a notch too high, for a book written in the 1980s—maybe more than a notch—and while the writing is sharp, sonorous and exact (cold ears, slippery leaves), those nods towards nature and eternity feel almost—

Embarrassing. That’s what Broyard was getting at, I think. The Transit of Venus asks a lot of its readers, but more than anything it asks them to conceive of themselves as potentially heroic, which means not as the center of attention but quite the opposite: as someone who might be incidental, whose own part in the drama of the world might require them (as indeed it does, for everybody) to die.

Three days after we came back from England, four after my teenage daughter and I were stopped on a street corner in London by a man who wanted us to sign a petition against knife crime (to her astonishment and my own, being from a place where “knife crime” might seem practically quaint), the Club Q shooting occurred in Colorado Springs, in the aftermath of which it became clear that qualities like “nobility” or “heroism,” those things that Shirley herself seemed to embody, aren’t actually in abeyance at all. They just tend to appear (as I suspect they always have) in people and places that tend not to aggrandize themselves as heroes or geniuses, and in places that the right—those people who like to gas on about “traditional” virtues of whatever kind—are unwilling and unable to see them.

Anyway, as we wind towards the holidays, and if you happen to find yourself browsing for a vacation read, both The Transit of Venus and Brigitta Olubas’s (wonderful! amazing!) biography of Shirley Hazzard are available wherever you seek to find them. I suggest that you do.

I’ll be back soon, with more (and with a tiny bit more of Shirley—albeit peripherally, and only in brief—in The Golden Hour, the cast of which is enormous). The pleasure of this newsletter is in its occasional nature—at least for me it is—but I’ve already got the next one in mind.

Yrs,

Matthew

p.s. Not much of a playlist this time around, but since I mentioned an English folk song—and since some of this plays into The Golden Hour’s soundtrack as well—here’s a hastily assembled baker’s dozen favorites, of late. It’ll sound great with your morning coffee, I promise.

p.p.s. I have a very few words in this morning’s New York Times Book Review, on Penny Wolin’s splendid book of photographs Guest Register. You made it this far, so what’s 300 more on a book I can also recommend wholeheartedly?

I, too, have TRANSIT on my nightstand, along with two back issues of The Atlantic, one of the more obscure Graham Greene titles (JOURNEY WITHOUT MAPS) and a Breece D'J Pancake collection of stories. With the business otherwise slowing to a holiday party-laden crawl over the next few days, I hereby vow to make that second attempt myself before the New Year. Thanks for the push!

The Transit of Venus still waits on my nite stand. I’m getting closer to beginning it again. It helps to know I’m in good company. Thanks for having faith in me. Xo MIL